- Home

- Creativation by NAMTA

- Membership

- NAMTA Connect Virtual

- About

- Resources

- Creative Outlook Market Research Study Report - MEMBERS ONLY

- Membership Directory - MEMBERS ONLY

- Meet the Independent Reps

- Meet the Creative Professionals

- New Products Page

- The STUDIO Recordings - MEMBERS ONLY

- Creative Products Certification Program (CPC)

- Retail Training Manuals

- NAMTA LOGOS

- Subscribe to Our Email List

- Discount Savings Programs

- Contact

- Advocacy

|

January 9, 2019 The Palette is available to all interested with an e-Subscription

On Painting, and Joy

Joy is unique among the good things in living. It is one of the differentiating qualities in life if you allow yourself to recognize it. Different from a state of being such as happiness, which often requires real work or some prerequisite of your doing, joy is unpredictable and unburdened. Needing only your recognition, joy is a gift offered up in the smallest and largest moments of our daily lives. Remarkably, joy can be experienced on our saddest, rainiest, darkest day if we are just willing to look for it. Like a sunburst, these moments are not meant to be permanent. As life itself, joy is fleeting. It is when a caterpillar first opens her wings, when the golden sun breaks through the stormy clouds, or when the sheer power of the storm excites you to the core. It is when the leaves of autumn shimmer in the steep angle of afternoon light, when “nature’s first green is gold, her hardest hue to hold,” or, when you recognize something nature brings forth that reminds you of a recently passed loved one as if it was that loved one embracing you. These are moments that are entirely gifted to us — and if we give ourselves permission to experience them — these are moments of joy. These are moments I attempt to cultivate in my paintings. I believe in the intrinsic value of this work. In large part I have dedicated my life to it, and it is my sincere hope that this work inspires you as nature herself does me. Fine Art Connoisseur

Rhapsody in Rainbow

Over the past 10 years, the Forbes Pigment Collection, housed at the Harvard Art Museums, has attracted a significant amount of attention. Held in a staff-only area of the museum, it can be viewed across the courtyard from the museum’s fifth floor. Enclosed by floor-to-ceiling windows, the pigment collection calls home a wall of cabinets installed during a 2014 renovation of the museum. The collection — arranged according to the exploded color wheel — is striking. Edward Walden Forbes started the collection in the early 1920s, and made it official in 1928. Originally, Forbes sought to create the pigment collection after purchasing a damaged Renaissance painting of the virgin and child. Hoping to restore the painting to its original brilliance, Forbes realized that he needed to understand the materials he was working with — and so the pigment collection was born. “The function of the pigment collection really hasn’t changed. It’s the same thing that it was for Forbes: it’s a set of analytical standards that are used to study and to help understand art and art making,” says Alison M. Cariens, the conservation coordinator for the Harvard Art museums. While the pigment collection may have ties to ancient history, the Harvard Art Museums and Strauss Center for Conservation and Technical Studies are dedicated to putting the collection to use in the present day. The collection is continually updated, and over the past few years, colors such as Surrey NanoSystems’s Vantablack (of which Anish Kapoor famously boasts sole artistic ownership) and Stuart Semple’s “pinkest pink” have been added. It’s a popular misconception that the collection is primarily used for artmaking. Although the Harvard Art Museums do significant work to repair and preserve their paintings via art conservation, the pigments are never directly added to a canvas. “We would never use them in conservation, because we want what our conservationists do to be distinct,” Cariens says. “Scientifically, visually. It’s not ethical to pretend that you are Van Gogh, because you’re not.” While its contents are never directly applied to canvases, the pigment collection’s principal aim is to facilitate art conservation. It actually spurred the hire of the first conservation scientists in the United States. And it forms a critical source of information when dissecting the history of any painting: “The pigment collection informs a lot of what we do that isn’t treatment-based. It informs the way that we are able to teach... It informs a lot of outside research, and a lot of the research we are doing here,” says Anne D. Schafer, paintings conservation fellow at the Strauss Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Sometimes, experts have used the collection to evaluate the legitimacy of a painting's attribution to any one artist. By analyzing the chemical makeup of the pigments used in a painting and comparing them to the known standards of the Forbes collection, analysts can determine whether the colors used would have been available to a specific artist during their lifetime, or if a pigment would be available in the region from which the painting is believed to have originated. One example is a painting purportedly by Jackson Pollock that went on the market a few years ago. “Everything aligned really well, like connoisseurship. Curators were saying this looks like it could be his stuff,” Cariens says. “But this lab ran tests of the pigments that were used, using these as a standard, and discovered that the red that was used was not available in art-making materials until 20 years after Jackson Pollock had died.” Some also consult the collection when classifying pigments. Sometimes the names are hard to distinguish — for instance, there are a dozen varieties of cerulean — while others are as eclectic as jelly bean flavors. According to Cariens, for instance, pink is “not historically a color,” but rather “the only color that only exists in our mind”: a reflection from each end of the visible light spectrum. The human eye takes in both red and violet or blue wavelengths and combines them. To name the color allows us to employ it — in our paintings, and, consequently, in conservation. Next time you find yourself in the lobby of the Fogg Museum, look up. You’ll find a kaleidoscope of color, each vial encapsulating a history of encounters between art and science. The Harvard Crimson

Meet the artist who put a realistic spin on comic book superheroes

Ross wields his superpower in his paintbrush, and he allowed CBS News' Anthony Mason into his secret lair. The little museum upstairs in Ross's home in the Chicago suburbs is every comic book fan's dream, filled with figurines, life-size superheroes and memorabilia. "This is making up for a life where I had to ask or beg for toys, and so once I had money then I could buy everything I ever wanted. And it just never stopped," Ross said. This is Alex Ross's world. He not only collects it, he creates it. In nearly 30 years as an artist and illustrator, he's painted almost every popular superhero. His work for DC was collected in the book "Mythology," and his work for Marvel has just been published in "Marvelocity." "It's kind of a difference based upon mood and vibe of the material. There's something about the stoic heroes of DC that could be contrasted against the hyperkinetic heroes of Marvel," Ross said. "I knew from whatever you might call a very early age this is what I wanted to do, period. I wanted to make art of superheroes. I wanted to, you know, sort of live in their skin full time if I could." As a kid, he began sketching his favorites, even making paper action figures, and found inspiration in his mother who was a fashion illustrator. "She became more my hero in the sense of watching her go off and work and giving me the idea of, hey, getting paid to do this. Not strictly just for the medium I wanted to be in, but just getting paid to draw," Ross said. Like his mom, Ross went to the American Academy of Art in Chicago, where he developed the realist style that would distinguish his superheroes. "It's supposed to respect kind of the history of the character going back to the original art style if the 40s," Ross said of his version of Superman. "This thicker, heavier version of the character, where he looked like he would really beat the living hell out of somebody was something that drew me in. There's something graphically interesting about the Joe Shuster art style that way." When Ross started in the late 80s, most comic book art was drawn and then inked in. But Ross wanted to paint his superheroes. "It's like you're getting more content added at you. More detail. More illumination of the subject. It's the same thing that you're taking out of seeing them in feature films now," Ross explained. Readers responded. He won the Comic Buyers Guide Fan Award for favorite painter seven years in a row and admits he wasn't surprised. "It's a terrible thing to say I wasn't, right? That's really egotistical. I'm sorry. … I feel like I was waiting for somebody to come and do this. And I'd been following comics my whole life and there had been these wonderful painted covers when I was a kid in the 70s that I just felt man, to read a whole story that would look like that on the inside would be fantastic. Well, nobody was doing that then." It has allowed Alex Ross to live the life he always imagined. "It means everything, you know? The fact that I would be intertwined with it, that it could fill my days, you know. That's the joy I still experience. I like to connect back to the person I was in that thing that gave me so much joy as a kid." CBS This Morning

Out of tragedy, a man finds his true calling

"I'm just creating. I'm just freeing my mind and what comes out is my true emotions," Davis told CBS News correspondent DeMarco Morgan. "It's a passion. It's an obsession. I love it that much. And I hope it shows in the work." That work includes landscapes, still lifes and portraits painted from a very different perspective: the 43-year-old paints with his mouth. When Davis was 19 years old, his friend shot him during a fight, leaving him paralyzed. He thought his life was over. "I didn't know anything about people in wheelchairs ... I didn't have a comprehension of the physical requirements of the daily living with somebody with that quality of life," he said. The teenager was placed in a nursing home to learn how to adjust to his new wheelchair-bound life. It was there that he met Juanita Butler. "I noticed him and I said, 'Oh, my god, you're so gorgeous. What are you doing here?' He says, 'I live here,'" she recalled. Butler told Davis she was going to get him out of there. She did, and a year later they married. "I made the best choice in the world when I said, 'I'm getting you out of this nursing home.' I found somebody who's so special, who's like a diamond in the rough, and now he's shining," Butler said. Shining through his art, something he's always loved but only really pursued after the incident. An occupational therapist suggested he try holding the brush with his mouth and after some convincing, he did. Fifteen years later, his paintings are recognized worldwide and range in price from $5,000 to more than $80,000. "Most don't believe it … because the level that I have gotten to in my artistry is where they say, 'You didn't paint that with your mouth,'" Davis said. He presented a portrait of former President Barack Obama to the man himself. "Oh, he loved it. The first response was 'I love that you didn't put the gray hair in there,'" Davis recalled. The artist also gives back. He volunteers his time to teach and inspire art students on Chicago's South Side at Richard J. Daley Community College. "I feel like me going out, mouth painting, showing the public, the community, that you can have a tragic accident, a tragedy that happened to you, and you could still be able to accomplish things," Davis said. Davis said he's never asked the question "why me" and instead has always dared to do better. He's even forgiven the man who shot him. "I have forgave that spirit behind it," he said. So his own spirit within could inspire those around him. "I just get up and I do what I do. Win the day. Win the week. Win the month. Win the year. Win your life," he said. Davis said the shooting was a blessing in disguise. Had he not been in the nursing home, he may not have met his wife, Juanita. And if he wasn't paralyzed, he may have never pursued his passion for art. CBS News

Vibrant Colored Pencil Drawings Filled in with the Colors of the Galaxy

From animal portraits to flashy sports cars, it seems there’s no end to what Kreutzer can draw. In one of her most recent pieces, the talented artist uses a combination of colored pencils and watercolor paint to render a giant, purple-hued moon. Rocky surfaces and lunar craters are detailed in a myriad of luscious, cosmic hues. In other works, Kreutzer creates a series of drawings depicting pairs of men’s Oxford-style shoes. “Shoes are possibly the most ubiquitous design item in history,” she says, “I love sketching them.” From shiny leather uppers to decorative stitching, each pair is so detailed, it looks like it could be lifted straight off the page. You can see more of Kreutzer’s incredible work on Instagram and buy limited edition prints via her website. My Modern Met

Hyatt's art store moving to Elmwood as online business grows

After 58 years, Hyatt's will close its store at 910 Main St. Saturday and relocate to a new, larger location at 1941 Elmwood Ave. on Jan. 24. Hyatt's Clarence store at 8565 Main St. will close for good the day before, on Jan. 23. It's a huge change for the art supply business that has been Buffalo's go-to place for art supplies for over half a century, and for the customers who have relied on Hyatt's inventory, expertise and friendly customer service. Ruth McCarthy carried two glass bottles through Hyatt's Monday afternoon – Gamsol and Galkyd Lite. A Hyatt's employee had taught her 10 years earlier how to use them together as the finishing touch on her oil paintings, and she has been doing it ever since. It's just one of many ways Hyatt's has helped her grow as an artist over the years. "They're terrific. They're all so knowledgeable and helpful," she said. "They've always been able to help me figure anything out." McCarthy is going to miss walking to the Main Street store from her home on Bryant Street. The new Elmwood Avenue location will be a haul from her studio at the Tri-Main Center but, as a customer of 40 years, she'll be sure to follow, she said. August Lascola, a surrealist painter who shares his tricks with McCarthy and other artists who come to shop, has worked at the Main Street store for 20 years. He's excited about the new location but, like everyone else, he's going to miss the old one. "It's 20 years, man. I'm anchored," he said. "It's gonna feel sad looking into this space when it's empty." Though he has always walked to work, he'll now have to take the No. 20 bus. He'll also have to start bringing lunch to work, because he'll no longer be able to hit Panaro's or any of his other restaurant hangouts. Tucked into a mix of industrial buildings and retail plazas near the Regal Cinemas Elmwood Center 16, the new location seems geared more toward cars and trucks than passersby. But, with the majority of Hyatt's business being done online and catering to customers around the globe, that makes sense. The move, which includes a larger retail area, will allow the new store to function more seamlessly as an online fulfillment center, with four loading docks and a lot more space for a shipping hub. "We're all really excited about taking this next step. We've been in business in what will be our 60th anniversary this year, and growing very rapidly for the past seven to 10 years," said Seth Martin, Hyatt's purchasing manager. "We outgrew our space on Main Street," he said. The new 42,000-square-foot location will be the largest independent art supply store in the country, Martin said. The space includes the retail store, warehouse and office space. The retail space will have 15,000 square feet, one-third more than the combined retail areas in the closing Buffalo and Clarence stores. Martin said it is "very likely" more people will be added to the company's workforce of 50. "The biggest thing I would say is that I think the new location is going to be really great for the entire Buffalo arts community and creative community," Martin said. "I think that because of all the space and all the things we do outside of the immediate area, we are able to offer a much larger selection, and a much deeper inventory than we otherwise would be able to." Hyatt's opened in 1959 on Franklin Street in a 200-square-foot storefront. The art supply business moved to Main Street in 1961, eventually expanding to take over four other retail spaces. As a result, the existing sales floor and behind-the-scenes spaces were pieced together and compartmentalized. The store has three floors and a mezzanine. The basement is made up of several different rooms rather than the open floor plan you might see in a warehouse. The new location, however, has everything on one floor and has a much more workflow-friendly layout. But the Elmwood store isn't just designed to make delivery trucks and online shoppers happy. There is plenty for brick-and-mortar customers to be excited about, too. The new digs will have room for expanded product lines, and more variety in products and package sizes. More colors of Gamblin oil paints will be available in larger tubes, for example. There will be enough room on shelves for the 8-ounce jars of Procion dyes, so customers won't have to ask an employee to get them from the basement. Classes will continue as well. The store will also have a more streamlined, polished look. It may even look downright fancy, with its new glass display counters. And, which may be most exciting for thrifty artists, there will also be a "scratch and dent" section, where customers can buy discounted merchandise that was returned by Amazon shoppers. And that's just the beginning. "A lot of our growing pains will be resolved," said Chris Piontkowski, a manager at the Main Street store. "Every time there was a new product it was like, 'Where are we gonna put this?' Now we have lots of space. It's exciting." Buffalo News

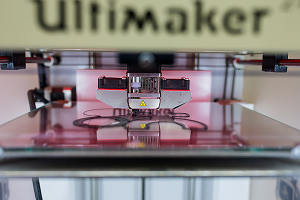

Art, Printed: Computers are redefining fine art. But is that a good thing?

If the idea of using computer software and a printer seems antithetical to fine art, it’s worth talking to third-year Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) student Zachery North. He’s an advocate for using 3D printing to make art and sees many reasons to embrace the technology. “I can much more easily correct or change things that don’t work. My work is very iterative and 3D helps me keep building on what I’ve done,” he says. “A lot of my work is experiential. I want people to be able to experience it and touch it. It’s not the traditional fine art gallery where people aren’t allowed to touch the art.” Some artists, fine art enthusiasts, and curators might be concerned that developing art via coding and pre-written algorithms is a poor substitute for more traditional artistic craftsmanship. But as more artists (and art school programs) work with 3D technology, concerns are lessening. “The art world in general is accepting of change, even if there is some grumbling,” says Brad Jirka, professor of fine arts at MCAD. “Some people worry that you lose the artist’s ‘hand’ in the artwork. But then they see exhibits where the 3D printing is used as a tool—an invisible component, often with analog tools—and the artist’s hand is there.” Christopher Atkins, the curator of exhibitions and public programs at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, feels the art potential with 3D printing goes beyond just technology. “Think of 3D printers the same way you think of charcoal or clay,” he says. “It’s elemental. It’s a tool for artists to use, just as people use clay to form ceramics.” 3D printing only dates back to the 1980s and has strong roots in Minnesota thanks to Eden Prairie–based Stratasys. The printers have greatly improved in quality and precision over time, which has expanded the types of products they’re used to produce. At first the devices were considered industrial in nature and were developed with an aim to create less-expensive manufacturing processes and parts. Eventually a wide variety of industries took to using the technology, from medical device companies to gun enthusiasts developing online designs for guns to be printed at home to NASA installing a 3D printer on the International Space Station for the printing of tools. As technicians and scientists were looking into the mechanical possibilities of 3D printing, artists were taking note of the technology’s artistic potential. At MCAD, students began exploring the tool decades before they could execute the actual printing. “The digital part of 3D came to MCAD in the late 1980s; we had an Intro to Digital Imaging class and slipped 3D modeling into that class,” Jirka says. “The first actual 3D printer arrived in 2000.” The process of 3D printing art varies depending on the artist but usually includes web-based modeling tools and/or scanning equipment to capture designs. Once captured, the designs are programmed into 3D-printing software to create a printing template. From there, the artist selects the desired materials for and scale of the piece, and ushers it into the final stages of actually printing. Unlike the ease of using a conventional printer, there’s a somewhat steep learning curve to using 3D printers—especially to create. “Even handing off the 3D models to printing machines requires some technical understanding,” says Duluth artist Jonathan Thunder. “You can expect to learn along [with] the process.” Challenges aside, 3D printing and modeling has enabled artists to pursue ventures previously unattainable. David Bowen used a drone above Lake Superior to photograph the lake, capture undulations of waves, and carve them into acrylic columns using a CNC router, which is similar to a 3D printer but uses a wood carver. Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s exhibit “Stranger Visions” featured 3D renderings of individuals’ faces developed from DNA she’d extracted from things like hair, chewed gum, and cigarette butts collected on the street and in public spaces. Beyond pushing artistic boundaries, 3D printing can also be used to overcome more basic limitations. Files of 3D sculptures can be sent to exhibit locations and printed on-site. After the show, the piece can be destroyed or donated. For the visually impaired, copies of famous sculptures provide an opportunity to engage with a piece that would otherwise be off limits. There’s also an archival application to the technology. MCAD’s 3D shop director Don Myhre creates models of buildings scheduled for demolition so they can be kept for posterity. Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari used 3D printing to create scale models of historical art and monuments destroyed by ISIS. Even the Smithsonian is using the medium: the organization is scanning their entire collection to use for research, education, and, for select items, to allow the public to 3D print and study them at home. At the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), curator and head of contemporary art Gabriel Ritter sees a world of possibility in 3D printing, and believes acceptance of the technology in art has largely arrived. “It’s an art form already accepted by collectors, especially those who like to have one foot in the future,” he says. “Museums are along for the ride, collectors are on board. It’s the embodiment of the future.” Not every museum is embracing 3D art with as much aplomb as Mia or The M. Both the Walker Art Center and Weisman Art Museum declined to be interviewed for this article, citing a lack of experience with the medium. More likely than not, though, the art form will eventually be accepted at museums as nothing out of the ordinary. According to Ritter, the art world is infinitely large enough to embrace tools traditional and new. “Artists will always use the tools available to them, and 3D printing is a tool,” he says. “It’s like when Ritter does have one concern about the new tool, though: the materials being used—namely, plastic. “What is the longevity of the materials used to print? The raw material varies from one printer to another. For a curator, that’s not the concern, as the curator focuses on form and ideas. But anyone involved in conservation sees it as a bigger issue. Will the sculptures brown, fade, melt?” It’s a fair question, and one that will eventually have to be addressed, but right now artists are still in the The experience of putting together the exhibit, called “Manifest’o” and running through July 2019, left Thunder in awe. “My own experience in the process is that I was able to bring something from the digital to our world, the real world, something born into the world out of creation. 3D—any single thing you can think of, just hit a button and it comes to life. It blows my mind. And that we can take a technical thing for devices and turn it into fine art—it’s a beautiful thing.” The Growler

Nine-story surrealist mural goes up on Mag Mile

The mural at 663 N. Michigan depicts people ascending a ladder to a lush world populated by flora, fauna—and a camera with a human eye. Monreal's previous Gucci work, which was also emblazoned on $1,400 sweatshirts, features intricately depicted characters inspired by old master painters including Hieronymus Bosch and John Everett Millais. The Michigan Avenue mural is not affiliated with the design house. Monreal creates his art using a computer or tablet; he doesn't take part in the actual mural painting. That process took about a month and required four to five painters at a time, according to Sydne Peck, who manages 663 N. Michigan on behalf of Cushman & Wakefield. The building's ground-level retail space is fully leased to Nike and Dylan's Candy Bar, though Dylan's lease is short-term and will be over later this year. Through a spokeswoman, Cushman & Wakefield declined to specify the terms of Dylan's lease. "Since 663 N. Michigan is in the center of the Magnificent Mile, we wanted to do something to really make it a landmark," Peck said. She said the mural will be up for at least six months. The mural, like others emblazoned on buildings across the city, is intended to draw Instagram influencers constantly on the hunt for new, vivid selfie backdrops—and, by extension, increased shopper foot traffic. Creating public art also helps fashion houses and retail strips better marry their bricks-and-mortar shops with the online world. "One of our initiatives in 2019 is to create identifiable spots that present classic selfie moments," said John Chikow, president and CEO of the Magnificent Mile Association, which partnered with Cushman & Wakefield on the mural. Chikow said the association did not contribute funding to the project. Peck declined to comment on how much Cushman & Wakefield paid for the mural or whether retail tenants contributed. Creating murals and other pieces of public art to draw shopper foot traffic is an increasingly popular strategy, according to Gil Eyal, CEO of Hyprbrands, a New York-based company that tracks social media influencers' reach and demographics so brands can partner with those who best align with their marketing goals. "There's a belief that this younger generation—millennials and younger—is no longer interested in walking into the store and getting the best price," he said. "It's about what emotions (shopping) evokes and whether it's the place to be. Being associated with the right people brings in the other right people." Eyal said art doesn't have any direct impact on the value of real estate, but may serve as "social (media) proof" to draw in potential new retail tenants. Still, there may be a downside in jumping on the mural trend. "They used to be very novel and very unique, but now they're popping up everywhere," he said. "And once you've seen it—or selfied it—it's done. Influencers are always on to the next thing." Crain's Chicago Business |

If I were a branch on that tree, it would be my desire to create little blossoms of color that you can bring into your life and home, which daily enable you the opportunity to experience and be reminded to look for joy.

If I were a branch on that tree, it would be my desire to create little blossoms of color that you can bring into your life and home, which daily enable you the opportunity to experience and be reminded to look for joy. What is the color of dragon blood? A dark, dusty red, at least according to the archives of the Forbes Pigment Collection. The legendary pigment was purportedly gathered from dragon wounds in the Middle Ages; more accurately, its color comes from tree resin. Conservation scientists at the Collection work to unlock the mystery of this centuries-old pigment, along with many other mystical colors.

What is the color of dragon blood? A dark, dusty red, at least according to the archives of the Forbes Pigment Collection. The legendary pigment was purportedly gathered from dragon wounds in the Middle Ages; more accurately, its color comes from tree resin. Conservation scientists at the Collection work to unlock the mystery of this centuries-old pigment, along with many other mystical colors. In the world of comic book artists, Alex Ross is a superhero. He's been called the Norman Rockwell of comics, putting his imprint on Superman, Spiderman, Aquaman and Captain America.

In the world of comic book artists, Alex Ross is a superhero. He's been called the Norman Rockwell of comics, putting his imprint on Superman, Spiderman, Aquaman and Captain America. Antonio Davis said his life was headed in the wrong direction when he was shot at close range and nearly killed 24 years ago. What he didn't know was that his life was about to take an extraordinary turn with purpose. Though paralyzed from the chest down, he became an accomplished painter.

Antonio Davis said his life was headed in the wrong direction when he was shot at close range and nearly killed 24 years ago. What he didn't know was that his life was about to take an extraordinary turn with purpose. Though paralyzed from the chest down, he became an accomplished painter. While some might consider colored pencils as mere art supplies for kids, more and more professional artists are using the common utensils to create awe-inspiring works that are a whole lot more than just childish scribbles. One creative to do so is Australian artist Georgina Kreutzer who creates vibrant, hyperrealistic color pencil drawings that showcase her incredible artistic skill.

While some might consider colored pencils as mere art supplies for kids, more and more professional artists are using the common utensils to create awe-inspiring works that are a whole lot more than just childish scribbles. One creative to do so is Australian artist Georgina Kreutzer who creates vibrant, hyperrealistic color pencil drawings that showcase her incredible artistic skill. It seems to be business as usual at Hyatt's All Things Creative. But everything in the attic above the bustling art supply store and everything in the basement below it has been cleared out. After Saturday, everything in the retail space will be gone, too.

It seems to be business as usual at Hyatt's All Things Creative. But everything in the attic above the bustling art supply store and everything in the basement below it has been cleared out. After Saturday, everything in the retail space will be gone, too. Watching a lumbering 3D printer slowly churn back and forth, painstakingly adding minute layer to minute layer of material to an ambiguous shape is far from exciting. It can take hours—sometimes days—until a final product reveals itself. But for as cumbersome as 3D printing can be, the technology has had a profound impact on the art world in recent years, affecting everything from how art is created to how it’s shared and consumed.

Watching a lumbering 3D printer slowly churn back and forth, painstakingly adding minute layer to minute layer of material to an ambiguous shape is far from exciting. It can take hours—sometimes days—until a final product reveals itself. But for as cumbersome as 3D printing can be, the technology has had a profound impact on the art world in recent years, affecting everything from how art is created to how it’s shared and consumed. Passersby on Michigan Avenue can now see a nine-story mural designed by Spanish artist Ignasi Monreal, who's also responsible for massive "art walls" commissioned by Gucci in New York, London, Milan, Hong Kong and Paris.

Passersby on Michigan Avenue can now see a nine-story mural designed by Spanish artist Ignasi Monreal, who's also responsible for massive "art walls" commissioned by Gucci in New York, London, Milan, Hong Kong and Paris.